Celiac.com 01/21/2026 - Many chemicals used in farming and manufacturing are designed to act on specific targets, such as weeds, insects, or fungi. However, people can still be exposed to small amounts of these chemicals through food, drinking water, household products, and environmental contamination. The researchers behind this study wanted to answer a straightforward question: can these widely used chemicals directly slow down or stop the growth of helpful bacteria that normally live in the human digestive tract?

This matters because gut bacteria support digestion, help train the immune system, and produce compounds that influence inflammation. If certain common chemicals unintentionally act like antibiotics, they could reshape the gut ecosystem in ways that affect health, especially for people who already have immune or digestive vulnerabilities.

How the Study Was Done

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

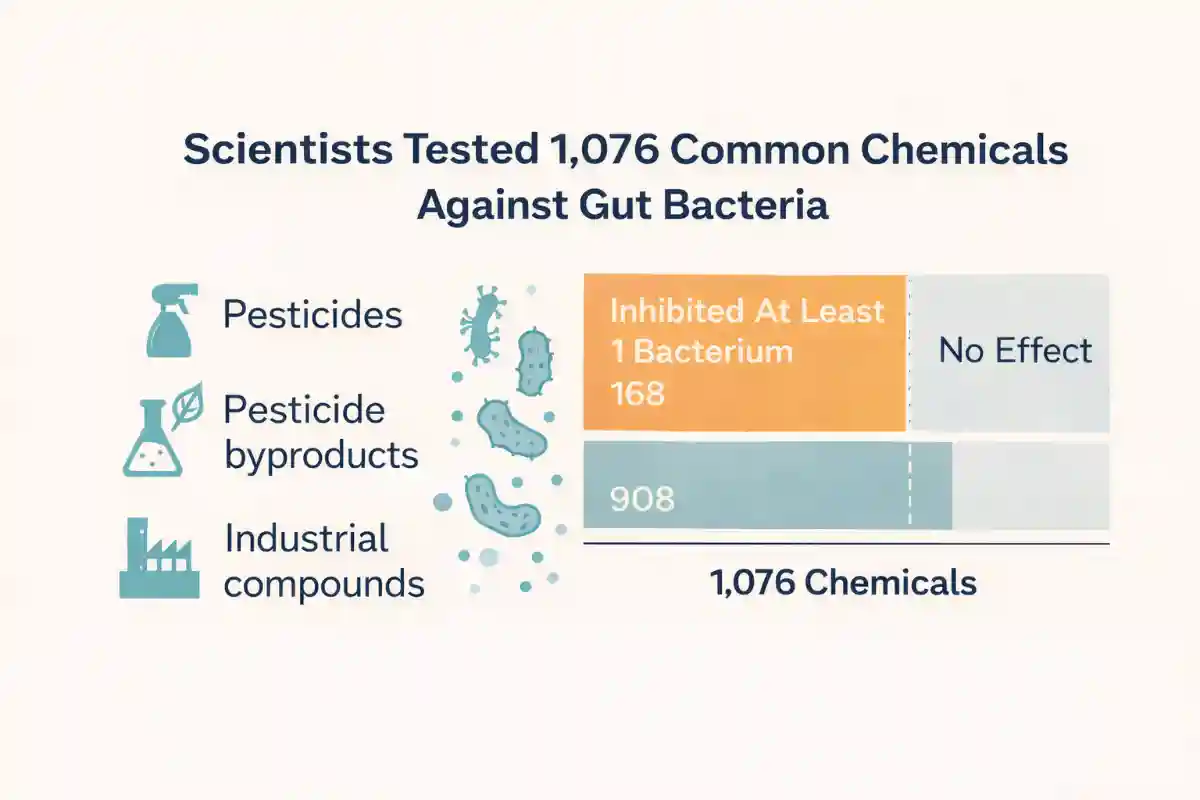

The research team created a large test library of chemical pollutants likely to enter food and water. This library included many types of pesticides, pesticide byproducts, and several industrial chemicals found in consumer goods or industrial processes. In total, the study examined 1,076 chemicals.

They then tested these chemicals against 22 bacterial strains representing 21 species that are common in healthy human guts. Each bacterium was grown under oxygen-free conditions similar to the digestive tract, and each chemical was tested at the same concentration. The researchers measured bacterial growth over a full day and compared growth to control conditions. A chemical was considered harmful to a bacterium if it consistently reduced growth beyond a preset threshold and passed statistical checks.

What They Found: Many Chemicals Reduced Gut Bacterial Growth

The headline result was that a significant portion of the tested chemicals could inhibit at least one gut bacterium. The researchers identified 588 meaningful chemical and bacterium inhibitory pairings involving 168 different chemicals. Most of these chemicals were not previously recognized for antibacterial effects, which suggests that antibiotic-like activity may be more common among environmental chemicals than many people assume.

The strongest overall impacts were seen among certain fungicides and industrial chemicals, with roughly three out of ten in those categories showing activity against at least one gut bacterium. In other words, some substances used to control fungi on crops or used in industrial applications behaved, in this laboratory setting, like agents that can suppress bacterial growth.

Which Gut Bacteria Were Most Sensitive

Not all bacteria responded the same way. Some groups were far more sensitive than others. Several bacteria in the Bacteroidales group showed higher sensitivity, and one of the most affected species in the screen was Parabacteroides distasonis. On the other end, some bacteria showed relatively strong resistance under the test conditions, including Escherichia coli, Fusobacterium nucleatum subspecies animalis, and Akkermansia muciniphila.

This uneven pattern is important because it suggests that chemical exposure might not simply reduce overall bacterial numbers. Instead, it could selectively suppress certain helpful species while allowing other species to persist, potentially shifting the gut community toward a different balance.

Why Concentration and Real-World Exposure Still Matter

A major question with any laboratory study is whether the dose resembles real life. The researchers selected a test concentration that has been used in other large chemical screening work. They also discussed evidence that some chemicals can reach levels in human blood that are within the same general range, and that concentrations inside the digestive tract may be similar or higher than what appears in blood for certain compounds.

That does not mean every person reaches these levels, or that every chemical behaves the same inside a complex human body. Still, the results support the idea that gut bacteria may plausibly encounter biologically active amounts of some pollutants, especially with repeated exposure over time.

Clues About How Bacteria Resist These Chemicals

To move beyond “what happens” into “why it happens,” the researchers ran additional experiments to identify bacterial features that influence vulnerability or resistance. In two gut bacteria species, they used large collections of mutants to see which genetic disruptions made bacteria more sensitive or more resistant when exposed to selected pollutants.

One key theme was the importance of bacterial export systems that pump toxic substances out of the cell. The study highlighted genes involved in these protective pathways, including a regulatory region known as acrR, as important for resisting pollutant stress. In simpler terms, bacteria that can more effectively eject harmful molecules may be better able to survive exposures that would otherwise stunt growth.

They also observed that certain pollutant exposures favored bacteria with changes in metabolic enzymes. One example involved a flame retardant called tetrabromobisphenol A, where the selected changes included genes tied to branched short-chain fatty acid production. This is notable because short-chain fatty acids are central to gut health and immune signaling, and changes in how bacteria make these compounds could have downstream effects even if bacteria survive.

Why These Findings Are Important Beyond Gut Health

The study raises two broad concerns. First, chemical safety testing often focuses on direct toxicity to human cells or to wildlife, but may overlook how chemicals influence the gut bacteria that help regulate immune function and inflammation. Second, if pollutants apply pressure similar to antibiotics, they could contribute to the broader problem of antimicrobial resistance by favoring bacteria with stronger defense systems, such as chemical export pumps.

The researchers also showed that, with enough data, it becomes possible to use computer-based prediction methods to forecast which pesticides are most likely to have antibiotic-like activity based on chemical structure. That could eventually help regulators and manufacturers identify higher-risk compounds earlier.

What This Could Mean for People With Celiac Disease

People with celiac disease already have a condition centered in the digestive tract, involving immune activation, intestinal inflammation, and changes in nutrient absorption when gluten exposure occurs. Many also pay close attention to factors that influence digestive symptoms and immune balance. This study does not claim that industrial or agricultural chemicals cause celiac disease, and it does not show that avoiding these chemicals treats celiac disease. However, it does highlight a realistic and important idea: substances people encounter through food and the environment may directly influence the growth and function of gut bacteria.

For someone with celiac disease, gut health is not a side issue. Even after adopting a gluten-free diet, recovery and symptom control can be influenced by the broader gut environment. If certain pollutants can selectively suppress helpful bacteria or alter bacterial metabolism, that could theoretically affect inflammation, digestion, and overall resilience. The practical takeaway is not panic, but awareness: maintaining gut health may involve more than just gluten avoidance, and future research may help clarify how environmental exposures interact with the gut ecosystem in people who have immune-driven intestinal disease.

Read more at: nature.com

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now