Celiac.com 01/26/2026 - This study explored a rare cell type in the human small intestine called the microfold cell. Microfold cells sit in specialized areas of the gut that sample material from the intestinal contents and help train the immune system. For many years, most detailed knowledge about these cells came from mouse experiments. The researchers set out to build a strong human-based model so they could learn what human microfold cells do, how they form, and whether they might play a direct role in the immune reaction to gluten that drives celiac disease.

Why Microfold Cells Matter in the Gut

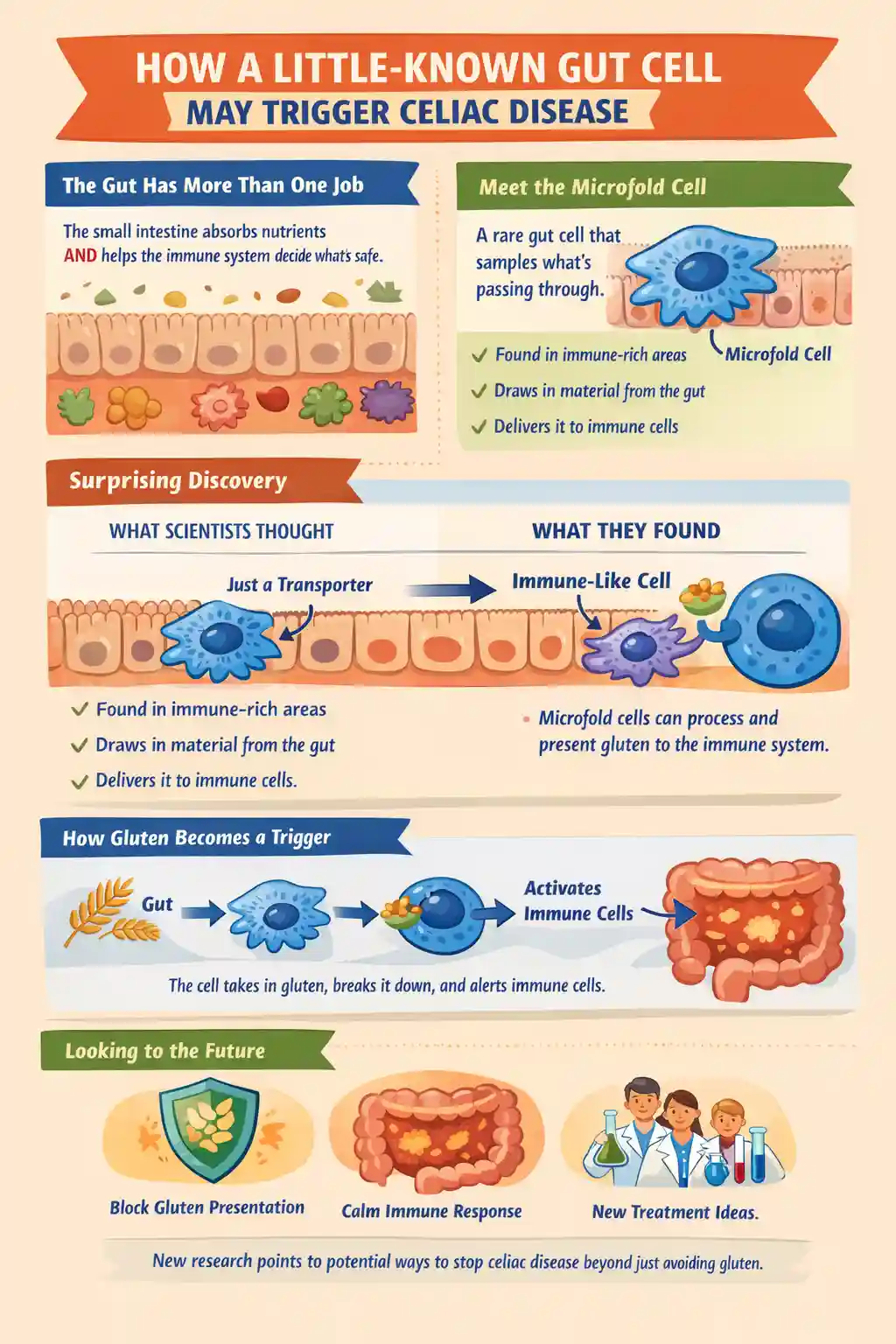

The small intestine has a difficult job: it must absorb nutrients efficiently while also detecting harmful microbes and other foreign substances. In certain immune-rich regions of the intestine, including structures called Peyer patches, the lining contains microfold cells that act like “sampling ports.” These cells help move material from the gut surface toward immune cells positioned underneath. Traditionally, microfold cells were thought to function mainly as transporters, handing off particles to professional immune cells that then decide whether to tolerate the material or mount an immune response.

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

However, celiac disease raises a key question: how does gluten, a food protein, become visible to immune cells in a way that leads to damaging inflammation in the small intestine? Understanding the earliest steps that bring gluten into contact with immune cells is central to understanding why celiac disease begins and how it might be prevented.

How the Researchers Studied Human Microfold Cells

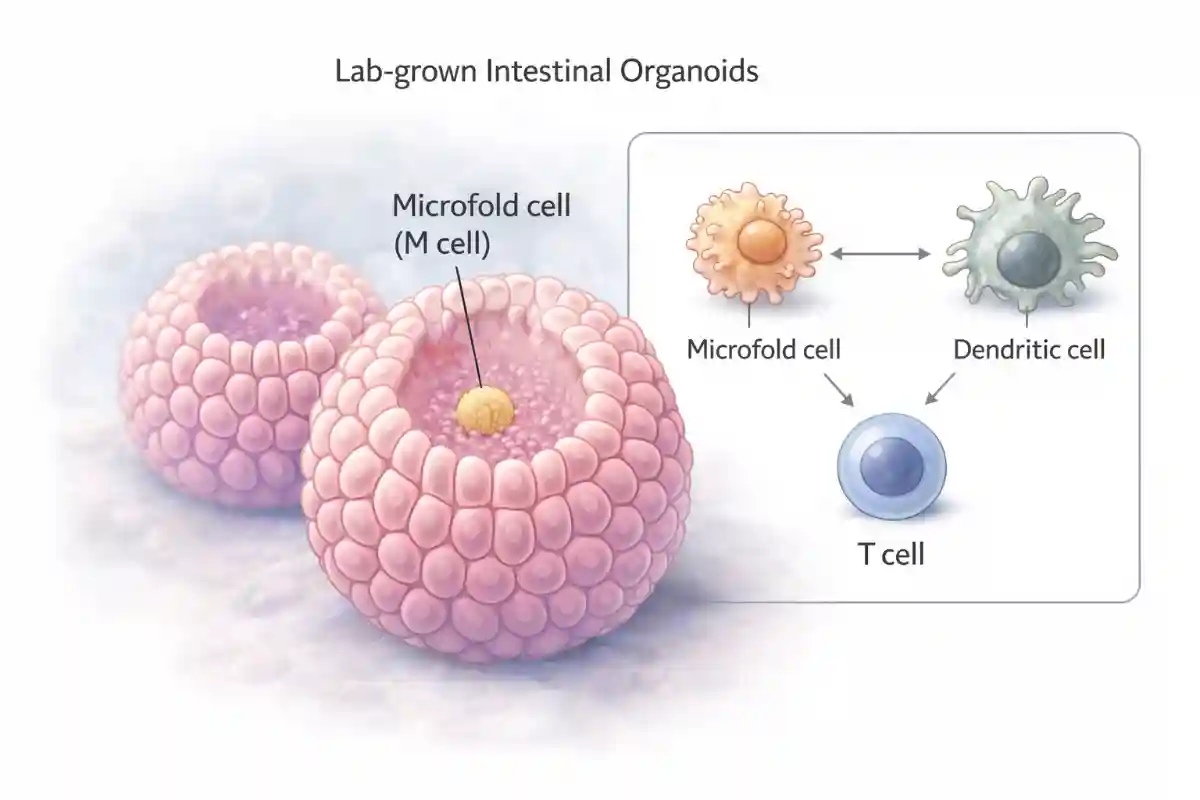

To study human microfold cells directly, the team developed an intestinal organoid system. Organoids are miniature tissue structures grown in the laboratory from human cells that can mimic key features of real organs. Using carefully designed growth conditions, the researchers were able to coax intestinal cells into forming microfold cells and then follow the developmental steps that lead to that identity.

They mapped the path of differentiation by examining patterns of gene activity across the developing cells. This allowed them to reconstruct a “developmental trajectory,” meaning a step-by-step view of how a typical intestinal cell becomes a microfold cell under the influence of specific signals. They also tested how these microfold cells behave by placing them in contact with immune cells, including gluten-responsive T lymphocytes, in controlled co-culture experiments.

Key Finding One: Human Microfold Cells Act More Like Immune Cells Than Expected

A central discovery was that human microfold cells share striking similarities with dendritic cells. Dendritic cells are immune cells famous for capturing antigens and presenting them to T lymphocytes. Antigens are small pieces of proteins that the immune system uses to recognize what is foreign. The researchers found that human microfold cells do not simply move material across the intestinal lining. Instead, they appear to take on features associated with antigen presentation, a function usually reserved for specialized immune cells.

In practical terms, this suggests that microfold cells may participate directly in the process of showing dietary or microbial proteins to the immune system, rather than serving only as a delivery route to other immune cells.

Key Finding Two: Signals That Drive Microfold Cell Formation Overlap With Immune Pathways

The study also identified signals and regulatory factors that promote the formation of microfold cells in the human model. The investigators reported that microfold cell development was induced by specific immune-related signals and required particular transcription factors that guide cell identity. This matters because it supports the idea that microfold cells are positioned at the intersection of the intestinal lining and the immune system, and that their development is closely tied to immune signaling networks.

By defining these developmental requirements, the study provides a clearer blueprint for how microfold cells arise in humans, which can help researchers build improved models and test interventions that either increase or decrease microfold cell activity depending on the clinical goal.

Key Finding Three: Human Microfold Cells Can Process and Present Gluten to T Lymphocytes

The most celiac-relevant finding is that microfold cells with the human leukocyte antigen DQ2.5 genetic background were able to process gluten and present gluten-derived antigen to gluten-responsive T lymphocytes in organoid and immune-cell co-culture experiments. In celiac disease, this genetic background is strongly associated with susceptibility because it helps the immune system bind and display certain gluten fragments to T lymphocytes.

Showing that microfold cells can perform this antigen presentation step is important because it places these cells much closer to the start of the disease process than previously appreciated. Instead of gluten needing to pass through multiple handoffs before reaching the critical immune recognition step, microfold cells themselves may contribute directly to the moment when gluten becomes “visible” to the immune system in a disease-triggering form.

What This Could Mean for Understanding Celiac Disease

Celiac disease involves a misdirected immune response to gluten that damages the lining of the small intestine. Many people think of the disease as an interaction between gluten, genetics, and immune cells. This study adds a new and potentially crucial participant: a specialized epithelial cell that is part of the intestinal barrier itself.

If microfold cells can present gluten antigen to T lymphocytes, then they may act as an early gateway that helps initiate or amplify the immune cascade. This does not mean microfold cells are the only route by which gluten reaches the immune system, but it suggests that microfold cells could be one of the most efficient or influential routes in susceptible individuals.

This perspective could also help explain why certain intestinal regions rich in immune structures are hotspots for immune activation. If microfold cells in these areas are especially capable of antigen presentation, then they may help shape whether the immune system becomes tolerant of dietary proteins or shifts toward inflammation.

Limitations and Next Questions

Because much of the work was performed in laboratory-grown tissue models, it will be important to confirm how often and how strongly this microfold-cell antigen presentation occurs in living human intestines. Laboratory systems are powerful because they allow controlled experiments, but they cannot perfectly capture every feature of a person’s complex gut environment, including microbiome influences, inflammation states, and long-term immune conditioning.

Future research will likely focus on questions such as:

- How frequently microfold cells present gluten antigen in people with and without celiac disease.

- Whether microfold cells become more active or more abundant during early disease development.

- Whether blocking microfold cell antigen presentation can reduce gluten-driven immune activation.

- How microbes and intestinal inflammation alter microfold cell behavior and antigen presentation.

Why This Study Could Be Meaningful for People With Celiac Disease

For people living with celiac disease, the only current proven treatment is strict lifelong gluten avoidance, which can be difficult and socially limiting. This study is meaningful because it identifies a specific human gut cell type that may participate directly in the earliest step that connects gluten exposure to harmful immune activation.

If future research confirms that microfold cells are a key gateway for gluten antigen presentation in susceptible individuals, that could open new paths for prevention and treatment. For example, therapies might be developed to reduce gluten antigen presentation at the intestinal surface, to modify microfold cell development in high-risk individuals, or to interrupt the interaction between microfold cells and gluten-reactive T lymphocytes. Even if such approaches are years away, pinpointing where gluten first becomes an immune trigger in the human gut is a major step toward more targeted solutions beyond dietary restriction alone.

Read more at: nature.com

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now