Celiac.com 11/28/2025 - For children with celiac disease, eating a strict gluten-free diet is not optional—it is the only way to prevent ongoing damage to the small intestine and support healthy growth. Yet gluten-free groceries and meals often cost more and are harder to find than wheat-based options. This study set out to understand how often families caring for a child with celiac disease struggle to access gluten-free food, which is called gluten-free food insecurity, and how those struggles affect health markers and day-to-day success with the gluten-free diet.

Goals of the Study

The researchers focused on three questions. First, how closely does gluten-free food insecurity line up with general household food insecurity among families of children with celiac disease. Second, which family or community factors are linked to gluten-free food insecurity. Third, does gluten-free food insecurity affect how quickly a child’s tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A levels return to normal after diagnosis, and does it affect adherence to the gluten-free diet.

How the Study Was Done

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

This was a single center cohort study conducted at a large pediatric medical center in the United States. The team identified all patients younger than eighteen years of age with a physician-confirmed diagnosis of celiac disease who were seen over a six-year span. Parents and caregivers received an electronic survey up to four times. The survey asked about gluten-free food insecurity, general food insecurity, adherence to the gluten-free diet, and common social barriers such as transportation, store access, and cost. Demographic information came from the medical record and the survey. Addresses were linked to a neighborhood material deprivation index to capture community-level disadvantage. Clinical records supplied laboratory values, including tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A over time, as well as visits with dietitians and referrals to social support services.

Who Responded

Surveys were sent to one thousand thirty-nine children from nine hundred ninety-four households, and about one in three households responded. Among respondents, most children were white and female, and the majority had a diagnosis of celiac disease confirmed by intestinal biopsy. Household incomes ranged widely, from less than sixty thousand dollars to more than one hundred fifty thousand dollars per year, and most families reported private health insurance.

How Common Was Gluten-Free Food Insecurity

Gluten-free food insecurity was common. About twenty-six percent of responding families reported gluten-free food insecurity, compared with about twenty percent who reported general food insecurity. When the researchers grouped families by both gluten-free and general food security status, a large majority were secure for both, but meaningful numbers fell into the two gluten-free food insecurity groups, including families that were otherwise food secure. This shows that access problems specific to gluten-free foods can exist even when a household has enough food overall.

Families who reported gluten-free food insecurity were more likely to live in neighborhoods with higher material deprivation scores and to have lower household incomes. Even so, gluten-free food insecurity was not limited to any single income bracket, suggesting that it should be considered across the board in clinical care.

Impact on Health Markers

The study examined how long it took for tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A levels to return to normal after diagnosis. Children from households with gluten-free food insecurity took significantly longer to normalize this blood marker than children from households without gluten-free food insecurity. In practical terms, this means prolonged ongoing immune activity triggered by gluten exposure, which likely reflects the daily difficulty of finding and affording safe gluten-free foods.

This relationship held true even after accounting for other factors in statistical models. Children who had multiple dietitian visits also took longer to normalize, which may reflect that persistent elevation in laboratory values prompts more intensive nutrition follow-up. There was no meaningful difference between groups in whether a child ever achieved normalization at any point; the difference was in the time required to reach that goal.

Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet and Real-World Barriers

Children from households with gluten-free food insecurity were significantly more likely to consume gluten. This included both frequent and occasional gluten exposure. When families described why gluten was consumed, the most common reason across the whole group was accidental exposure. Among those with gluten-free food insecurity, several barriers stood out: the higher price of gluten-free foods at grocery stores and restaurants, difficulty accessing stores or restaurants that carry safe options, and transportation challenges. Personal preference and the reality of social settings also contributed, but cost and access were the strongest and most consistent drivers linked with gluten-free food insecurity.

Social and Clinical Context

Families reporting gluten-free food insecurity were more likely to have been referred to social work, but most still had not received such help. The study did not find consistent differences by age at diagnosis, body mass index, race or ethnicity distributions among respondents, or routine specialty follow-up. Importantly, nonresponding households tended to live in areas with greater material deprivation, which suggests that the observed rate of gluten-free food insecurity may be an underestimate.

What These Findings Mean for Families and Clinics

The take-home message is straightforward. Gluten-free food insecurity is common for families of children with celiac disease, and it has measurable clinical consequences. Children in this situation take longer to quiet the immune response to gluten, and they face more frequent gluten exposures because cost, transportation, and access get in the way of perfect adherence. These are not merely individual willpower problems; they are structural barriers.

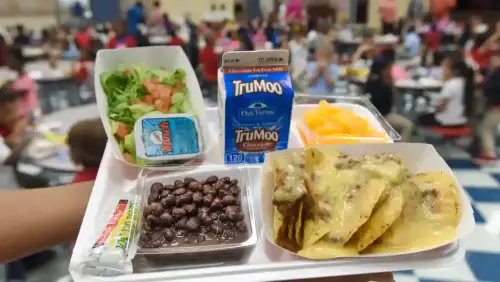

Routine screening for gluten-free food insecurity should be part of pediatric celiac disease care. Practical help can include connecting families with food assistance programs that stock certified gluten-free staples, offering vouchers or discount programs where available, providing lists of local, affordable sources of safe foods, helping families plan lower-cost gluten-free meals, and advocating for schools and community programs to carry safe options. When care teams ask about these realities and act on what they learn, children are more likely to succeed on the gluten-free diet and recover faster.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths include a large pediatric cohort, linkage of survey answers to medical records and laboratory trends, and analysis that separated gluten-free food insecurity from general food insecurity. Limitations include a response rate of about one third, electronic distribution that may miss families with limited internet or phone access, and conduct at a single medical center. The survey was offered only in English, and the number of respondents identifying as Black was very small, which limits conclusions about racial differences. These factors mean the true rate of gluten-free food insecurity could be even higher than reported.

Why This Matters to People Living With Celiac Disease

For families managing celiac disease, the study validates a lived truth: doing the gluten-free diet well depends not only on knowledge and motivation, but also on whether safe food is available, affordable, and close by. When those supports are missing, children are more likely to be exposed to gluten and to have a slower drop in tissue transglutaminase immunoglobulin A, extending the period of intestinal irritation. Recognizing gluten-free food insecurity as a health issue encourages clinics, schools, food assistance programs, and communities to respond with concrete solutions. That can mean shorter times to healing, fewer symptoms, and less stress for families.

Conclusion

Gluten-free food insecurity affects about one in four families of children with celiac disease in this study and is linked with slower improvement in key laboratory measures and lower adherence to the gluten-free diet. Screening and targeted support should become routine parts of care. Addressing cost, transportation, and access is not just a kindness; it is a pathway to faster healing and better daily life for children who must live gluten-free.

Read more at: onlinelibrary.wiley.com

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now