Celiac.com 01/05/2026 - Celiac disease is an immune-driven condition in which the body responds aggressively to gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. This reaction damages the small intestine, leads to painful symptoms, and causes long-term health complications if untreated. At present, the only effective therapy is a lifelong gluten-free diet. For many people, this diet is expensive, restrictive, and difficult to follow perfectly. Even tiny amounts of gluten can trigger symptoms and intestinal injury.

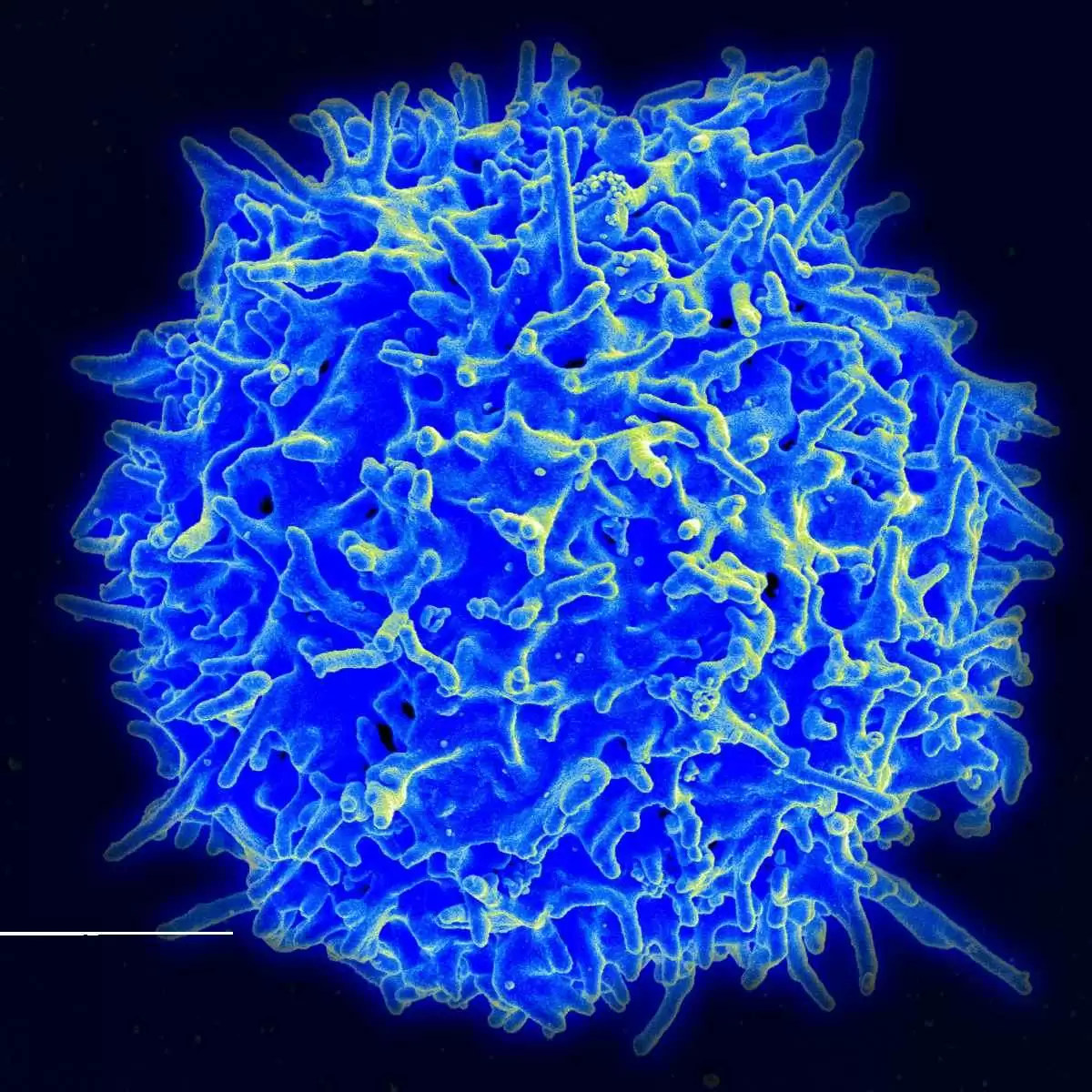

A new study offers a glimpse into what future treatments might look like. Instead of avoiding gluten entirely, scientists explored whether it might be possible to retrain the immune system so it does not attack the body when gluten appears. Their approach involves modifying a special group of immune cells called regulatory T cells—cells whose natural role is to calm down excessive immune responses. The researchers found that carefully engineered versions of these cells were able to reduce gluten-driven immune reactions in animal models. While early, the findings suggest a new path toward treatments that address the root cause of celiac disease.

Understanding the Immune Players in Celiac Disease

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

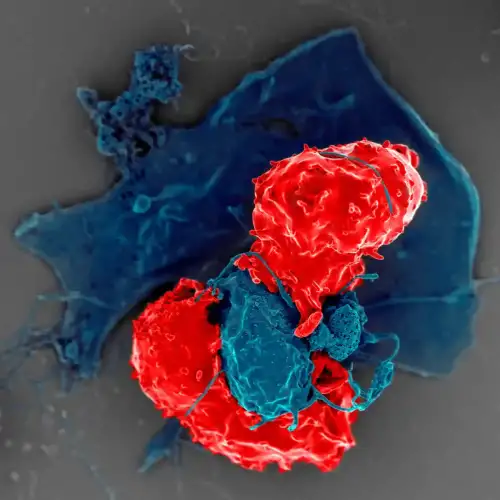

The immune system contains many different kinds of cells. In celiac disease, a type of cell known as an effector T cell drives the harmful reaction. These cells recognize gluten as if it were dangerous and launch an attack that damages the lining of the small intestine.

Another type of cell, called a regulatory T cell, normally helps prevent the immune system from overreacting. In healthy individuals, regulatory T cells help maintain balance by slowing or stopping immune responses when they are no longer needed. In celiac disease, however, the natural regulatory T cell response is not strong enough to counteract the aggressive behavior of effector T cells.

The study explored whether increasing or improving regulatory T cells could calm the immune system when gluten is present.

Precision Editing of Regulatory T Cells

Researchers used an advanced gene-editing technique to modify regulatory T cells and effector T cells so that each responded to very specific gluten fragments. They selected two gluten fragments that trigger strong immune reactions in most people with celiac disease. These fragments bind to a genetic marker called HLA-DQ2.5, a marker carried by the majority of celiac patients.

The scientists replaced the natural T cell receptors on the engineered cells with new receptors designed to recognize these gluten fragments precisely. This process allowed the modified regulatory T cells to become highly targeted: they could sense when gluten-reactive effector T cells were activated and then suppress their activity.

Testing the Therapy in a Mouse Model

To understand how these engineered cells behave inside a living system, the research team used mice bred to express the same human genetic marker associated with celiac disease. The team created two groups of engineered cells:

- Effector T cells that reacted strongly to gluten

- Regulatory T cells designed to suppress these reactions

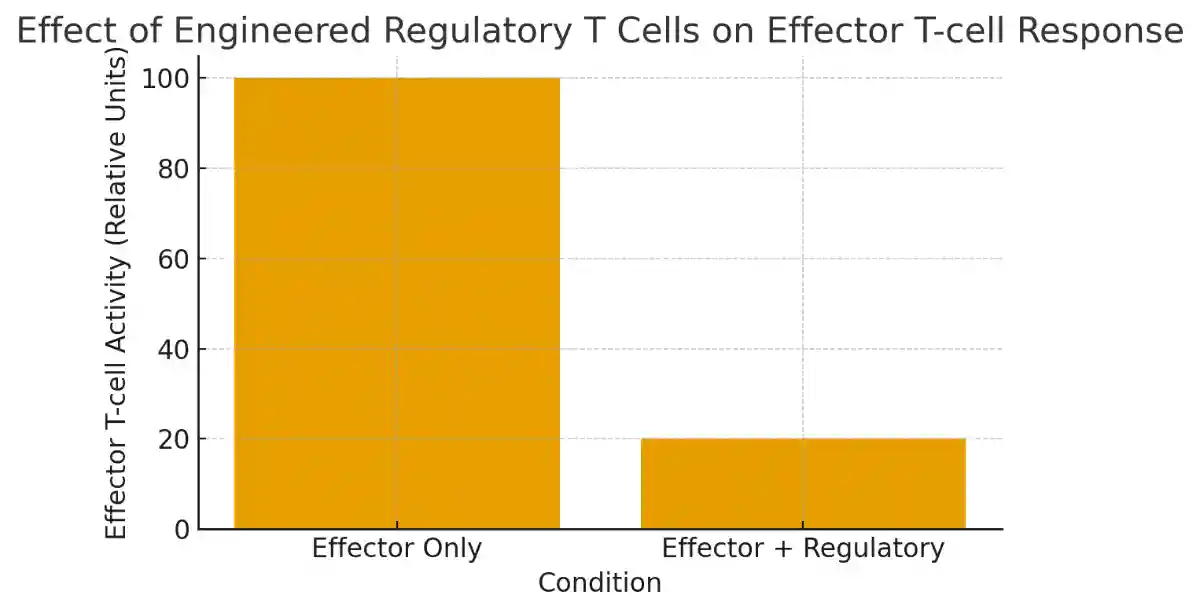

Both types of engineered cells were introduced into the mice. When the mice were later given gluten, the effector T cells quickly moved toward the intestines and began to multiply—exactly as they do in human celiac disease.

However, when mice received the engineered regulatory T cells, the reaction changed dramatically. The dangerous effector T cells did not expand or travel to the gut. The regulatory T cells were able to shut down the response before it caused harm. This calming effect did not require the regulatory T cells to match the exact gluten fragment the effector cells were reacting to. Instead, the regulatory cells suppressed a broad range of gluten-related immune responses, a phenomenon known as bystander suppression.

Why Bystander Suppression Matters

Celiac disease is complicated because people do not react to just one gluten fragment—they respond to many. A major challenge in designing therapies is the wide variety of gluten proteins that can activate disease-causing immune cells.

The engineered regulatory T cells showed the ability to suppress effector cells targeting not only the same gluten fragment but also different, related fragments. This suggests that a therapy based on these engineered cells could calm the entire network of gluten-reactive immune responses, not just one narrow pathway.

Limitations and Questions for Future Research

While the study is encouraging, experts note several limitations that must be addressed before human trials become possible. The work was performed in mice, which do not naturally develop intestinal damage from gluten the way humans with celiac disease do. The experiment also tested gluten only once instead of repeatedly, so long-term effects remain unknown.

Additionally, people with celiac disease sometimes have fewer regulatory T cells, and in some cases those cells are less functional. It is not yet clear whether engineered regulatory T cells would behave the same way in a person whose immune system is already dysregulated.

More research is needed to understand when such a therapy would be most effective—for example, whether it should be used before symptoms develop or after the disease is already established.

What This Study Suggests for the Future

Despite the challenges, this research lays important groundwork. The approach adapts principles from cell therapies already being used in cancer treatment, raising the possibility that similar techniques could eventually help people with autoimmune diseases. The idea of restoring immune balance—rather than merely avoiding triggers—is an appealing shift.

If future studies support these findings, engineered regulatory T cells could one day help people with celiac disease tolerate accidental gluten exposure, reduce intestinal inflammation, or perhaps even allow a more flexible diet. For many patients, this could dramatically improve quality of life.

Why It Matters for People with Celiac Disease

The results of this study are particularly hopeful for those living with celiac disease. Current treatment relies entirely on dietary restriction, which is difficult to maintain and does not fully prevent complications for everyone. A therapy that calms the immune system’s reaction at its source could offer a deeper level of control over the disease.

While this research represents only an early step, it points toward a future in which celiac disease might be managed not by avoiding gluten completely, but by restoring harmony within the immune system itself. For patients and families affected by celiac disease, this possibility represents an exciting and meaningful shift in how the condition might one day be treated.

Read more at: science.org

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now