Celiac.com 05/30/2020 - Recently, I posted a query to ICORS Listserv’s celiac email group listing the following symptoms of hypochondria as found on the Mayo Clinic website:

- Excessive fear or anxiety about having a particular disease or condition.

- Worry that minor symptoms mean you have a serious illness.

- Seeking repeated medical exams or consultations.

- “Doctor shopping,” or frequently switching doctors.

- Frustration with doctors or medical care.

- Strained social relationships.

- Obsessive medical research.

- Emotional distress.

- Frequent checking of your body for problems, such as lumps or sores.

- Frequent checking of vital signs, such as pulse or blood pressure.

- Inability to be reassured by medical exams.

- Thinking you have a disease after reading or hearing about it.

- Avoidance of situations that make you feel anxious, such as being in a hospital.

The response from people on the Listserv was immediate and most of them reflected my own experience on the long road to diagnosis. Some responded with gratitude and relief that they were not alone and named their “symptoms” by number.

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

“I too am guilty of 1, 2, 3, 4 sort of, 5 still am, 6-even my friends thought I was a little over the top, 7-still to this day, 8 never goes away, 11 wondering if the doctors actually have the right diagnosis. After all it took them this long to come up with it.”

“As far as the hypochondria list—I’m guilty of: 3 4 5 6 11 & 13.”

“I have not been treated for hypochondria, but I know people who were beginning to say it was all in my head. I suffered from 3, 5, 11 and 12. It took me nearly 8-10 years before they finally diagnosed me with celiac disease. My mother-in-law went through the same thing until they diagnosed her thyroid condition. After awhile, you’re afraid the doctors are going to see and think, “Oh, no! Not her again! What does she think she might have now?” ”

There were many others who listed numbers or told their story. This is my story about the long road to a celiac disease diagnosis:

I was 42 years old and had been incapacitated for thirteen years by the time I was diagnosed with celiac disease. My husband’s jobs in retail moved us so often (eight cities in thirteen years) that I had seen nearly two dozen doctors including a gynecologist, a rheumatologist and at least one family doctor in each city. At the time of my diagnosis, I’d suffered over a decade from pain, severe fatigue, and anxiety as well as cognitive trouble that made me unemployable. The question of digestive irregularity was sometimes brought up and dismissed as a nervous reaction. My biggest concern, though, by far, was the drastic loss of cognitive function. After I’d seen about a dozen doctors, I became savvy enough to quit bringing up my fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue diagnoses (the mention of which garnered responses anywhere from lip-tightening to eye-rolling, followed by anti-depressant prescriptions). I never admitted to my first diagnosis which was hypochondria.

After the birth of my last child, I began my quest for relief. I saw a neurologist first, with the following complaints: My short-term memory was non-existent; I had severe fatigue; I had a severely impaired sense of direction, and; my reading and comprehension had slowed markedly. Attending art school had become difficult because my visual memory seemed to have gone missing. I could no longer hold a picture in my head between viewing the object and turning back to the paper to draw it. The bonus of a tremor made my line-quality suffer which was extremely disheartening. I couldn’t control line-width by subtle variation of pressure of the chalk on paper.

At home, completing mundane tasks required an outsized effort and was extremely frustrating. I couldn’t remember a phone number long enough to dial it without referring back to it two or three times. More often than not, I became confused and had to start dialing all over. I frequently got lost in my own town while driving, and I began stammering in stressful situations.

At the neurologist’s office, I was given an EEG which showed no indication of nerve impairment. Although my quality of life was annihilated, my neurologist was not impressed with my symptoms. I was a 27-year-old mother of two small children, he said, as he looked at his watch and suggested that I get some rest and a psychiatric evaluation.

I was naïve. I thought that by getting an evaluation I would prove that I was earnestly looking for an answer. I made an appointment with a psychiatrist to give me the exam. The test was exhausting; it went on for hours. There was a long questionnaire that asked, several times in different ways, whether I ever heard voices or believed people were following me. I was asked many times, each time in slightly different way, what my most fervent desire was. My answer was always that I wanted to get well.

After the questionnaire, I was given a round of verbal tests, that involved word recall and some non verbal tests that involved drawing pictures and assembling puzzles. I had a very hard time finding synonyms and naming objects, but my puzzles went together very quickly, I was told.

When I went back to the neurologist he said that because of the psychiatric report, diagnosing hypochondria, I wasn’t a suitable patient and he could do nothing for me.

I tried to believe in the possibility that I did, indeed, have hypochondria. At least that was something I could be responsible for; something over which I could take control. Raised with a belief in the ability of the mind to affect the body, I looked into the disease of hypochondriasis. I was desperate to help myself so I researched our home medical encyclopedia (this was a while before the Internet) and bought a book on the subject of hypochondria. I learned that it was then considered a fairly rare illness, and that real hypochondriacs drew some benefit from the sympathy they received due to the perception they are ill. That was far from the case with me.

On the verge of a divorce because my husband hadn’t yet come around to believing that I was actually ill, I was getting no sympathy from him or his family. My siblings found it more convenient to believe I was either lazy or exaggerating my complaints than to do anything to help with my two small boys. My parents, who believed me, were too elderly and ill to help much, but my mother would send over the occasional roast beef dinner which I received with tears of gratitude. I rejected the concept of hypochondria when I saw that there was absolutely nothing in it for me, and wondered who in the world could possibly benefit from such a mindset.

When I received a bill from the psychiatrist, I wrote him to insist on a copy of my test results. He was very reluctant, and told me I might not like what I found. I told him he might not get paid if I didn’t have the access to my file. His one-paragraph evaluation stated that although there was a big discrepancy between my verbal skills and sorting tests, and although I did seem to want to get well, since I still complained and nothing was found, I was a hypochondriac. In other words, the results of the hours of expensive testing were discounted and he made a diagnosis based on the fact that I had no other diagnosis. I, too, discounted the value of the test by refusing to pay for it.

The weeks dragged into years. Many days I was so weak that I could only lock myself and my toddlers in my bedroom with diapers, baby food and formula and lie on the floor with them. Just trying to stay conscious to make sure they didn’t hurt themselves required a monumental effort. Often, I was too ill to prepare even a sandwich for myself. Periods lost in this type of exhaustion continued on and off for over a decade until my eighth gynecologist discovered the pain in my outer abdomen. I admitted to having long bouts of diarrhea that I had sometimes been unable to control.

He insisted that before I leave the exam room that I get an appointment with a gastroenterologist whom he knew to be very competent. Before I left, I had an appointment in hand, written on a prescription sheet. I can’t express the warmth and gratitude I still feel toward this doctor who took my health so seriously when I’d come to feel so disposable.

A few weeks later, I was diagnosed with celiac disease and started the arduous journey toward a completely gluten-free diet, the only treatment yet available. I saw a significant improvement just 12 hours into the diet, and thought my suffering was over.

It wasn’t. I had become ill with Graves’ disease which my family doctor was unwilling to diagnose. After a few weeks with a heartbeat at 144 beats per minute, I asked to be referred to an endocrinologist who ordered new labs. I put my arm out for another prick, tried to breathe slowly, and decided to stop at Barnes and Noble on the way home to buy a book so I could read up on diagnostic criteria. By this time in my life, I’d become quite unwilling to trust my health to any one person.

It may well be that I am here today because I took the initiative to do a little of my own research. My first endocrinologist misread my lab results and declared that I was getting better and suggested a “wait and see” approach. While I was on the phone, I tried to remain calm despite the hammering in my chest and the excruciating sense of urgency spreading across my throat. I calmly, if haltingly, asked for the numbers of my new test results.

The man had read the results wrong. He thought they were getting better, but because he compared results from two different labs, he hadn’t perceived that both sets of lab results showed a non-existent production of thyroid stimulating hormone, a sure sign that my thyroid was in overdrive.

After asking for a second opinion, I was diagnosed with Graves’ disease and finally, after four months of agony, put on anti-thyroid drugs which returned me to a state of relative normalcy. Graves’ disease, before the invention of these drugs, by the way, had a 50% survival rate. I could just as easily be dead today.

Naturally, when I consider the years I lost when my boys were small, I still get angry. I wonder if my physically talented son, Patrick, would have been a baseball star had I been able to cheer him on at his games. I wonder whether more time with Stevie puttering in the garden and encouraging his extraordinary love of natural science would have invested him with more self-confidence. Perhaps that would have made his middle school years less excruciating. I would have loved to visit my older daughter in Manhattan and taken in a show once in a while, but was always too weak when it came time to live up to my plans. I wish I had been able to finish my schooling and get a job to help take the load off my husband who has been the sole breadwinner for all of our marriage.

I carry all of these regrets in the pain in my back, I believe, and still look forward to the day I can lay them down.

In the early stages, after the Graves’ diagnosis, a rage ran through me that burned like poison in my veins. The tens of thousands of dollars that were wasted on tests, the snide comments and the derisive looks from medical professionals, friends, neighbors and family still boil in the back of my consciousness. I started to write to every doctor that had failed me, then threw the letters away, knowing they’d just take me for a hysteric, and simply consider my case anecdotal. I started goading my friends into questioning their doctors and getting second opinions. I saw undiagnosed celiac disease or Graves’ disease in nearly everyone I met.

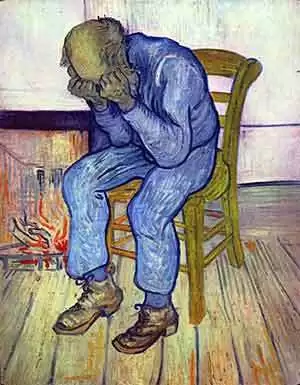

Then something, something beyond will or intent, something deep within me broke. I realized that my trials, my ill health, my burdenhood were really not my fault. Yes, yes, all this time I’d been telling myself this truth, but now the clouds of recrimination and responsibility were actually parting. Finally, after several years of righteous anger and indignation, for the first time, I allowed myself to grieve over my lost years of health. I began to realize how, even though I fought tooth and nail against the idea that my illness was all in my head, that the very perception of me as weak-minded had the power to alter my perception of myself. This was a true epiphany. My mother had taught me that if I was doing the right thing, that the opinions of other people meant nothing, but after being told so many times that it was normal to be tired, or that I had occult depression, or lectured that I should not let myself get stressed out, I had begun to feel like someone who couldn’t be trusted no matter how trustworthy I was. I had become the mythical Cassandra’s twin sister.

My story is far from unique. When the dozens of people who responded to my inquiry on the Listserv shared their stories, I began to see a pattern of systemic failure in our medical system. Some of these stories can only be described as horrific.

Kat Fury, who responded with a thoughtful email, told me how she suffered agony for years before she was finally diagnosed with celiac disease and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome type 3. She had this to say:

By the time I was five I had learned to not complain about things hurting me or the dislocation of my limbs. My parents didn’t believe in doctors, but having enough of my being “lazy, depressed, and bulimic” they had me hospitalized in a psychiatric ward for said symptoms. This confirmed my worst fear, that I was crazy and that everyone felt this kind of daily pain. Even though I couldn’t keep my food down sometimes, and the pain of both disorders was unbearable, I rarely complained. During my stay in the psychiatric facility I met a girl with a diagnosis of Reynaud’s Syndrome, a circulatory disorder. When I learned about it I discovered I also had all of her symptoms, usually worse. I made the mistake of saying something and was punished by being put into solitary confinement for a week.

Kat was eventually diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a rare genetic mutation that causes her to have inadequate collagen and be overly flexible. Before her diagnosis she once got dismissed from work after being caught trying to put her shoulder back into its socket. She was told not to come back without a doctor’s note. Because of her intense guilt over not being able to handle her aches and pains, she misunderstood. She thought she had been fired and she never returned to her job. The incompetent treatment she received as a medical patient left her with psychological wounds so severe she couldn’t even take her own dislocated shoulder seriously.

She went on to describe how her EDS diagnosis made doctors reluctant to treat her broken back after a car accident. She is now permanently unable to walk unassisted. Her mistreatment defies comprehension. She related this insight “…my body has many things considered rare, but the more I investigate my genetic propensity for these diseases, the more I learn they are only rare because of a systemic failure to diagnose.” … If my doctors had stopped using the saying ‘When you hear hoof beats think horses not zebras’ I would’ve had a better childhood.”

Unfortunately, those who have celiac disease, thyroid disease and Ehlers Danlos syndrome are not alone. Patients with difficult to diagnose autoimmune disease are all at terrible risk of permanent damage to their health because of delays in diagnosis and treatment. There seems to be no standard of care in place to look beyond the horses to find the zebras. Drug companies, who have made themselves the physicians’ source of new information and medical advancement, have no interest in talking about diseases for which there is no drug currently under patent. The current practice of confining office visits to eight-minutes, along with insurance company pressure to limit testing, it is likely that anyone who doesn’t have a popular illness with textbook symptoms is going to get shunted aside and labeled “hypochondriac.”

This label serves many functions. It aids in the loss of family support, replacing it with disgust, which makes it more difficult for the patient to believe in herself, or continue to bother her doctor with her concerns. Labeling a complaining patient as a hypochondriac allows the doctor to feel antipathy instead of sympathy, which is efficient and cost-effective because it releases the doctor from any obligation to do the time-consuming research needed to follow up on her case. In the big picture, creating a culture that makes this apocryphal diagnosis so very pervasive makes patients more likely to change doctors, which results in more first-visit charges, which are usually more than double the price of a regular office visit. Hence, every doctor’s coffers are fortified.

We like to think that our doctors think like Dr. House on the TV series…that they won’t give up on us until they figure out what is really wrong, that when they rule out the common diseases, they will follow the trail to the less common sources of symptoms, but this is rarely the case. Any time a patient is given a diagnosis of exclusion, that ends in the word “syndrome,” that means your doctor has given up. Fibromyalgia syndrome is one of these. No known etiology, a vague collection of symptoms, no further need to research once cancer and Crohn’s disease are ruled out. The same goes for “irritable bowel syndrome.” Although there are plenty of expensive drugs to treat it, it isn’t an actual disease, it’s a medical stalemate. Perhaps you actually have small intestinal bacterial overgrowth or an intestinal yeast infection, or God forbid, celiac disease. Most patients will never know, because there are plenty of expensive new drugs on the market that treat and mask only the symptoms.

Hypochondria may be a real psychiatric condition, but its diagnosis depends on the black and white determination that there really is nothing physically wrong with the patient. Otherwise, it is perfectly understandable that a curious, pro-active person would try again and again to get help, and investigate her symptoms. To tell a patient conclusively that there is nothing wrong with her requires a burden of proof that is insurmountable, since not every disease is immediately diagnosable and not every disease is well-known. The fair thing to say would be something along the lines of: “I’m at the limits of my capability to help you,” or, more honestly, “Digging any deeper into the cause of your malaise is more than I care to do.”

The cracks in the system are becoming more noticeable. Because of patient awareness and activism, conditions once thought to be rare, such as celiac disease, are now known to be common. When I was diagnosed with celiac disease in 2002, it was thought to have a prevalence of one in 4200 people in the general population. It is now known to affect around one in a hundred. Other recent examples are the greatly increased prevalence of thyroid disease, vitamin D and vitamin B12 deficiencies. Any of these can cause an array of vague but debilitating symptoms, such as generalized pain and chronic fatigue. Yet the suspicion of hypochondria is always at the forefront. This should not be the case. Such a diagnosis has a terrible impact on the patient’s mental and physical health. It should be considered with the greatest of caution instead of flung, like monkey-product, in arrogance. This egregious mistake violates both the spirit and the letter of the Hippocratic Oath, “First, do no harm.”

If, as the Mayo site suggests, hypochondria diagnoses occur at a rate of between one and five percent of all patients, consider this: Celiac disease and thyroid diseases occur at rates of one percent and at least five percent respectively. These two severely under-diagnosed conditions alone pretty much take care of the alleged prevalence of hypochondria in the general population. Add to those patients anyone else with difficult-to-diagnose ailments such as lupus, multiple sclerosis or any of the dozens of other autoimmune diseases less familiar to the family practitioner, and we are easily past the full suspected five percent. For these reasons, it is high time we sent the diagnosis of hypochondria to the dust-bin of history.

Recommended Comments

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now