-Yes, there’s more to life than rice and corn!

Variety, it’s been said, is the spice of life. So what’s a person to do when they’re told to eliminate wheat and/or gluten from their diet? Most turn to rice, corn, and potatoes—an adequate set of starches, but ones that are sorely lacking in nutrients, flavor, and imagination.

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

The superheroes of gluten-free grains are often referred to as “ancient” or alternative grains, which are loaded with nutrients and unique, interesting flavors. The following is a condensed excerpt from my newly published book, Wheat-Free, Worry-Free: The Art of Happy, Healthy, Gluten-Free Living.

“Alternative” Grains: The Superheroes of Gluten-Free Grains

If you’re an adventuresome eater, you’re in for a treat. In searching for alternatives to wheat, rye, or barley, you’ll discover a variety of wheat-free/gluten-free grains that you may never have heard of before, many of them loaded with nutrients and robust flavors not found in typical grains like wheat and rice. If you’re not the adventurous type and you just long for the ease of a few tried-and-true favorites, you’ll find them here as well.

Perhaps you fall into still another category—you’ve been eating a wheat or gluten-free diet for a while and you think you already know everything there is to know. Okay, what’s quinoa, and how the heck is it pronounced? Is teff wheat-free? Do Job’s Tears have religious significance? If you don’t know the answers to these questions, or if you think ragi is a spaghetti sauce and sorghum is what you get when you have your teeth cleaned, it’s time to move on to lesson one.

Alternative Grains and Non-Grains

Even if you can’t eat wheat, rye, barley, or oats, there are several other grains, fruits, and legumes that are not only acceptable alternatives to them, but they also happen to be loaded with flavor and nutrients. Here are some of the many choices available to those on a wheat and gluten-free diet (WF/gluten-free):

- Amaranth (WF/gluten-free)

- Buckwheat/groats/kasha (WF/gluten-free)

- Cassava (arrowroot) (WF/gluten-free)

- Chickpea (garbanzo) (WF/gluten-free)

- Job’s Tears (WF/gluten-free)

- Millet (WF/gluten-free)

- Montina (WF/gluten-free)

- Oats (WF/gluten-free, but oats can be contaminated with wheat and other grains)

- Quinoa (WF/gluten-free)

- Ragi (WF/gluten-free)

- Rice (WF/gluten-free; only brown rice is whole grain)

- Sorghum (WF/gluten-free)

- Soy (WF/gluten-free)

- Tapioca (WF/gluten-free)

- Taro root (WF/gluten-free)

- Teff (WF/gluten-free)

Many of the proteins found in these alternatives are a great source of complex carbohydrates. The fuel from these carbohydrates, found in plant kingdom starches, produces what nutritionists call a protein-sparing effect, which means the body can meet its energy requirements without dipping into its protein reserves.

Several of these alternative grains and non-grains are high in lysine, an amino acid that controls protein absorption in the body. Because this amino acid is absent from most grains, the protein fraction of those grains is utilized only if eaten in conjunction with other foods that do contain lysine. All high protein grains are better utilized by the body when they are eaten with high-lysine foods such as peas, beans, amaranth, or buckwheat.

Amaranth (WF/gluten-free): Loaded with fiber and more protein than any traditional grain, amaranth is nutritious and delicious, with a pleasant peppery flavor. The name means “not withering,” or more literally, “immortal.” While it may not make you immortal, it is extremely healthful, especially with its high lysine and iron content.

Buckwheat (groat; kasha) (WF/gluten-free): It sounds as though it would be closely related to wheat, but buckwheat is not related to wheat at all. In fact, it’s not even a grain; it’s a fruit of the Fagopyrum genus, a distant cousin of garden-variety rhubarb, and its seed is the plant’s strong point. The buckwheat seed has a three-cornered shell that contains a pale kernel known as a “groat.” In one form or another, groats have been used as food by people since the 10th century b.c.

Nutritionally, buckwheat is a powerhouse. It contains a high proportion of all eight essential amino acids, which the body doesn’t make itself but are still essential for keeping the body functioning. In that way, buckwheat is closer to being a complete protein than any other plant source.

Whole white buckwheat is naturally dried and has a delicate flavor that makes it a good stand-in for rice or pasta. Kasha is the name given to roasted hulled buckwheat kernels. Kasha is toasted in an oven and tossed by hand until the kernels develop a deep tan color, nutlike flavor, and a slightly scorched smell.

Be aware, however, that buckwheat is sometimes combined with wheat. Read labels carefully before purchasing buckwheat products.

Millet (WF/gluten-free): Millet is said by some to be more ancient than any grain that grows. Where it was first cultivated is disputed, but native legends tell of a wild strain known as Job’s Tears that grows in the Philippines and sprouted “at the dawn of time.”

Millet is still well respected in Africa, India, and China, where it is considered a staple. Here in the United States, it is raised almost exclusively for hay, fodder, and birdseed. One might consider that to be a waste, especially when considering its high vitamin and mineral content. Rich in phosphorus, iron, calcium, riboflavin, and niacin, a cup of cooked millet has nearly as much protein as wheat. It is also high in lysine—higher than rice, corn, or oats.

Millet is officially a member of the Gramineae (grass) family and as such is related to montina.

Montina (Indian Rice Grass) (WF/gluten-free): Indian rice grass was a dietary staple of Native American cultures in the Southwest and north through Montana and into Canada more than 7,000 years ago, even before maize (corn) was cultivated. Similar to maize, montina was a good substitute during years when maize crops failed or game was in short supply. It has a hearty flavor, and is loaded with fiber and protein.

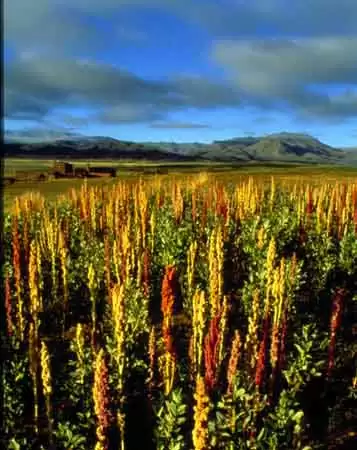

Quinoa (“KEEN-wah”) (WF/gluten-free): The National Academy of Science described quinoa as “the most nearly perfect source of protein from the vegetable kingdom.” Although new to North Americans, it has been cultivated in the South American Andes since at least 3000 b.c. Ancient Incas called this annual plant “the mother grain,” because it was self-perpetuating and ever-bearing. They honored it as a sacred food product, since a steady diet appeared to ensure a full, long life; and the Inca ruler himself planted the first row of quinoa each season with a gold spade.

Like amaranth, quinoa is packed with lysine and other amino acids that make a protein complete. Quinoa is also high in phosphorus, calcium, iron, vitamin E, and assorted B vitamins. Technically a fruit of the Chenopodium herb family, quinoa is usually pale yellow in color, but also comes in pink, orange, red, purple, and black.

Quinoa’s only fault is a bitter coating of saponins its seeds. The coating comes off with thorough rinsing prior to cooking, and some companies have developed ways to remove the coating prior to delivering quinoa to stores.

Sorghum (milo) (WF/gluten-free): Sorghum is another of the oldest known grains, and has been a major source of nutrition in Africa and India for years. Now grown in the United States, sorghum is generating excitement as a gluten-free insoluble fiber.

Because sorghum’s protein and starch are more slowly digested than that of other cereals, it may be beneficial to diabetics and healthy for anyone. Sorghum fans boast of its bland flavor and light color, which don’t alter the taste or look of foods when used in place of wheat flour. Many cooks suggest combining sorghum with soybean flour.

Soy and Soybeans (WF/gluten-free): Like the ancient foods mentioned at the beginning of this section, soy has been around for centuries. In China, soybeans have been grown since the 11th century b.c., and are still one of the country’s most important crops. Soybeans weren’t cultivated in the United States until the early 1800s, yet today are one of this country’s highest yielding producers.

Soybeans are a legume, belonging to the pea family. Comprised of nearly 50 percent protein, 25 percent oil, and 25 percent carbohydrate, they have earned a reputation as being extremely nutritious. They are also an excellent source of essential fatty acids, which are not produced by the body, but are essential to its functioning nonetheless.

Teff (WF/gluten-free): Considered a basic part of the Ethiopian diet, teff is relatively new to Americans. Five times richer in calcium, iron, and potassium than any other grain, teff also contains substantial amounts of protein and soluble and insoluble fiber. Considered a nutritional powerhouse, it has a sweet, nutty flavor. Teff grows in many different varieties and colors, but in the United States only the ivory, brown, and reddish-tan varieties can be found. The reddish teff is reserved for purveyors of Ethiopian restaurants, who are delighted to have an American source for their beloved grain.

A Word About Sprouted Grains

Some people believe that “sprouted grains,” even ones that contain gluten such as wheat, are gluten-free—not true! The sprouting process sparks a chemical reaction that begins to break down gluten, so some people who are slightly sensitive to gluten may find that they can tolerate sprouted grains better, but too many of the peptides that are reactive for celiacs are still present, so sprouted grains are not safe for people with celiac disease or gluten intolerance.

Recommended Comments