Celiac.com 01/19/2026 - This six-month study explored whether removing gluten from the diet could influence disease progression, inflammation, and body composition in women living with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis is a long-term autoimmune condition in which the immune system attacks the brain and spinal cord, leading to inflammation, nerve damage, and gradual disability. Because the course of the disease can vary greatly from person to person, researchers have become increasingly interested in whether dietary approaches might help reduce inflammation or slow disease-related changes.

The researchers focused on a gluten-free eating pattern, which is essential for people with celiac disease but is sometimes followed by others with autoimmune conditions. The goal was to see whether avoiding gluten could reduce markers of inflammation in the blood, improve physical measurements such as weight and waist size, and lead to measurable improvements in neurological disability.

Why Diet and the Gut Matter in Autoimmune Disease

Celiac.com Sponsor (A12):

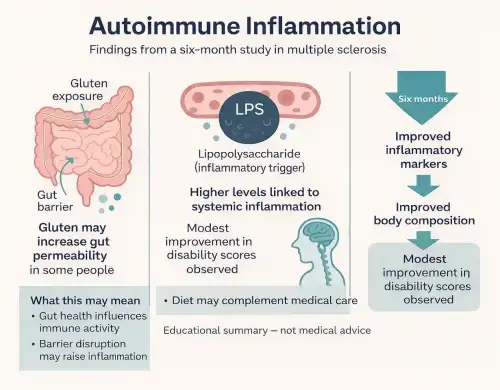

Growing research suggests that the digestive system plays an important role in immune health. The gut is home to trillions of bacteria that help digest food, support the immune system, and protect against harmful microbes. When the balance of these bacteria is disrupted, harmful substances produced by certain bacteria can leak into the bloodstream and trigger inflammation throughout the body.

One such substance is lipopolysaccharide, a component of the outer wall of certain bacteria. When elevated in the bloodstream, it is known to stimulate immune responses and promote inflammation. In autoimmune diseases, chronic exposure to inflammatory triggers like this may worsen disease activity. Gluten has been suggested as one possible contributor to increased intestinal permeability, allowing inflammatory substances to pass more easily from the gut into the blood.

How the Study Was Conducted

The study followed fifty-four adult women diagnosed with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis over a six-month period. Participants were divided into two equal groups. One group followed a structured gluten-free diet, receiving education about gluten-containing foods along with personalized meal plans based on individual preferences and living circumstances. The second group continued eating gluten but was given general advice on healthy eating, without specific restrictions.

Researchers collected detailed information at the beginning of the study, after three months, and again after six months. This included body weight, body mass index, waist and hip measurements, body fat levels, dietary intake, and blood samples. Disability related to multiple sclerosis was measured using a standardized neurological scale designed to track changes in physical function over time.

Changes in Inflammation and Immune Activity

One of the most important findings involved blood levels of lipopolysaccharide, a marker linked to inflammation originating in the gut. Women who followed the gluten-free diet showed a clear and meaningful reduction in these levels over the six-month period. In contrast, those who continued eating gluten tended to show stable or increased levels.

This reduction suggests that removing gluten may have improved gut barrier function or altered the balance of gut bacteria in a way that reduced inflammatory signals entering the bloodstream. Lower levels of systemic inflammation may be particularly important in autoimmune diseases, where ongoing immune activation contributes to tissue damage.

Effects on Disability and Disease Progression

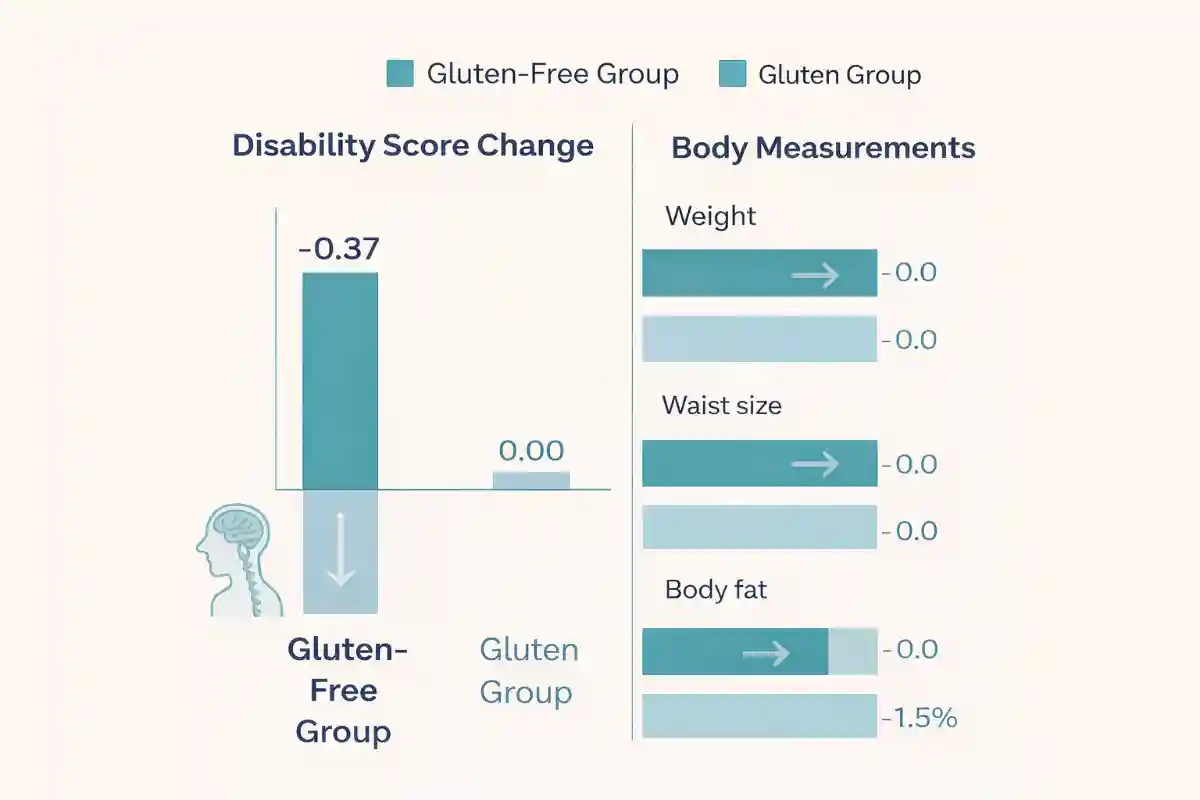

Disability related to multiple sclerosis was assessed at the beginning and end of the study. Participants on the gluten-free diet experienced a modest but statistically meaningful improvement in disability scores. This indicates slightly better neurological function or fewer physical limitations after six months. In comparison, the group that continued eating gluten showed no measurable change in disability.

Although the improvement was small, it is notable because multiple sclerosis typically follows a progressive course over time. Any intervention that stabilizes or slightly improves physical function may be clinically meaningful, especially when added alongside standard medical treatment.

Improvements in Weight and Body Composition

Women in the gluten-free group also experienced significant improvements in body weight and related measurements. On average, they lost weight, reduced waist and hip circumference, and decreased overall body fat. Importantly, lean body mass was preserved, suggesting that weight loss reflected healthier changes rather than muscle loss.

These changes were not seen in the group that continued eating gluten. Excess body fat is known to promote inflammation, and weight reduction alone may help lower inflammatory burden. The combination of improved body composition and reduced inflammatory markers suggests that the dietary intervention had multiple beneficial effects.

Dietary Changes Observed During the Study

Participants following the gluten-free diet consumed fewer calories and fewer carbohydrates over time. This shift may have contributed to weight loss and metabolic improvements. Intake of protein, fat, fiber, and most vitamins remained stable, suggesting that the diet was nutritionally adequate when properly planned. A small decrease in vitamin A intake was noted, highlighting the importance of careful dietary guidance when eliminating food groups.

These findings emphasize that a gluten-free diet does not simply remove gluten-containing foods, but often changes overall eating patterns. With appropriate education and planning, it can support weight management without leading to major nutrient deficiencies.

Limitations and Considerations

The study had several limitations that should be considered. It included only women and followed participants for six months, which limits conclusions about long-term effects or applicability to men. The number of participants was relatively small, and adherence to a gluten-free diet can be challenging, particularly in cultures where grain-based foods are common.

Additionally, while the findings show associations between the gluten-free diet and improved outcomes, they do not prove that gluten alone was responsible for all observed benefits. Weight loss, changes in food quality, and other lifestyle factors may also have contributed.

Why This Study Matters for People With Celiac Disease

For people with celiac disease, this study offers important reassurance and broader context. A gluten-free diet is medically necessary for celiac disease to prevent intestinal damage and long-term complications. This research suggests that the benefits of gluten avoidance may extend beyond the gut and influence systemic inflammation and immune activity.

The findings support the idea that gluten can play a role in inflammatory processes affecting the nervous system and immune regulation. For individuals with celiac disease who also experience neurological symptoms or have concerns about autoimmune conditions, this study adds to growing evidence that strict adherence to a gluten-free diet may have wide-ranging health benefits.

While people with celiac disease should not view this research as proof that a gluten-free diet prevents or treats other autoimmune diseases, it reinforces the importance of maintaining dietary compliance and highlights the powerful connection between gut health, inflammation, and overall well-being.

Read more at: sciencedirect.com

Recommended Comments

There are no comments to display.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now